Aon Catastrophe Analyst Chris Swann was one of two runners up in the 2021 Aon Scholarship. The topic of his essay below is '2050 Climate Change: Industry Impacts, Challenges and Opportunities'.

Why did we not act sooner?

Our window of opportunity to change the course of climate change 30 years ago with radical and collective solutions was wide open.

Net zero emission targets for 2050 had been supported by 110 countries, representing 65 per cent of global carbon dioxide emissions; the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy was beginning; improvements in electrifying mass transit were in place; and developments in green infrastructure by smart urban planning was no longer just an idea.

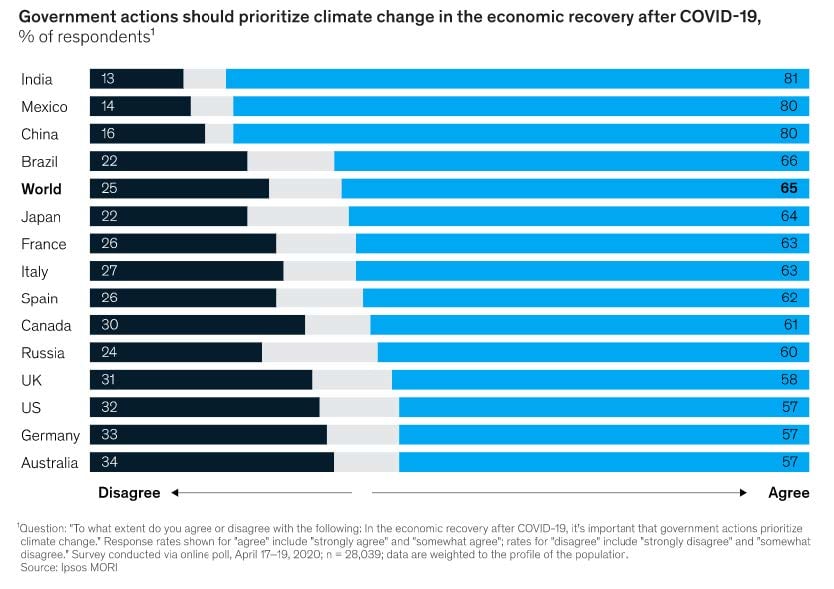

Public opinion also favoured government prioritisation of climate change post the COVID-19 pandemic (see Appendix A), and research told us that a low carbon recovery from 2020 would have created five times more jobs per million dollars invested, compared to spending on non-renewable energy.

Appendix A (McKinsey and Company, 2020)

People across the world even saw first-hand what a fall in global nitrogen dioxide levels looked like during the pandemic.

The Himalayan mountains were visible from northern India for the first time in 30 years, and uncommon wildlife re-entered transparent Venice canals.

So why is it that despite strong scientific indications and observable evidence at that time, did the world not become proactive or consistent in acting on climate change?

The answer, a combination of reduced political attention, environmental policy paralysis, the continual delay of environmental regulations in the interest of economic growth, and depressed oil prices, which have made low-carbon technologies less competitive, among many other things.

Numerous global industries and businesses have been investigated for their myopic and undedicated response to climate change.

It is of little surprise that the (re)insurance industry is one to be scrutinised, given its stagnation in pioneering solutions, having failed to properly appreciate the existential threat to the financial system climate change represented.

The slow-moving nature of the industry and lack of responsiveness since 2020 has damaged its reputation and credibility as a global economic citizen, however it remains in a unique position as (re)insurers indemnify insureds for climate-related damage and fund the economy through substantial investment portfolios.

Worst case scenario

Unfortunately, our worst-case predictions from three decades ago are being realised today, with more change already set in motion.

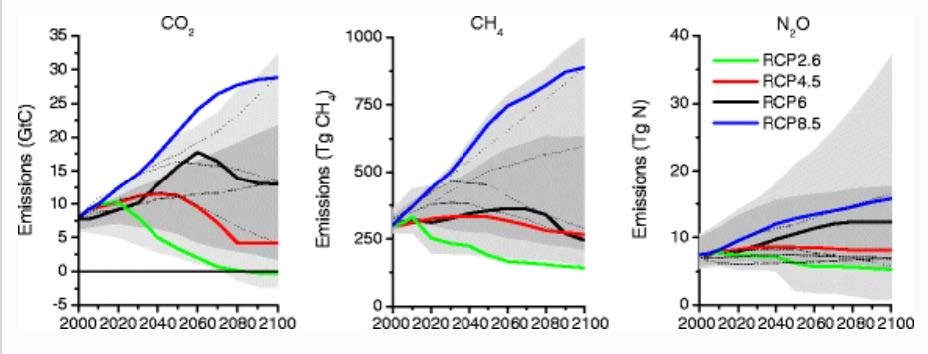

Of the four representative concentration pathway’s (RCP) from 2010, we are most closely aligned with the 8.5 scenario, which predicted between 15 to 20 gigatons of carbon emissions in the atmosphere by 2050, and approximately 25 to 30 gigatons by 2100 (see Appendix B).

Appendix B (Van Vuuren, et al, 2011)

The impact of this warming in Australia today has increased extreme heat events and dangerous pyro convection conditions, in combination with a decreased frequency but increased intensity of tropical cyclones.

In Florida, sea levels have risen 2.5 feet since 2000 which has caused tidal flooding in the state to surge from a few days in 2019 to more than 200 in 2050.

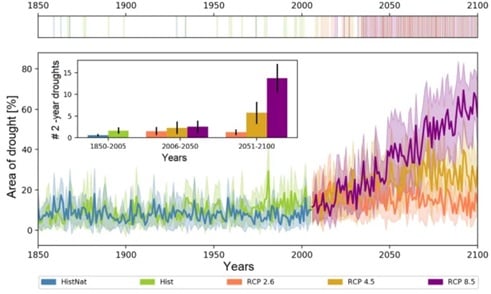

And European consecutive year droughts which were once one-in-250-year events have increased sevenfold (see Appendix C).

Appendix C (Vittal Hari, et al, 2020)

(Re)insurers now more than ever need to take a strategic approach to climate risks across all facets of their business to revitalise the long-term viability of the industry.

Prior experiences of complex catastrophe years provide critical learning opportunities today.

In the early 21st century, the (re)insurance industry grappled with some of the largest insured catastrophes in history.

Hurricane Katrina caused US$82.3 billion in insured losses in 2005; devastating flooding in 2011 resulted in US$16.3 billion worth of loss in Thailand; and Australia experienced one of the worst bushfire seasons on record killing more than a billion animals in 2019.

There was also a rise in compounded extreme events which caused localised physical damage and cascading secondary global fiscal impacts beyond the event source.

2020 epitomised this, as a highly complex catastrophe year, with 28 separate billion-dollar insured loss events, together with the coronavirus pandemic.

We learned the unique difficulty of planning and initiating responses in such situations, and the extent to which compounded catastrophes cause devastating feedback loops that cripple economies and lead to prolonged human suffering.

In the face of growing and emerging risks from climate change, it is vital (re)insurance companies enhance their climate response by implementing learnings across underwriting, commercial, technical and societal perspectives.

Underwriters in 2050 are being challenged by stakeholders such as customers, shareholders and regulators, to broaden the relevance of the industry beyond traditional risk transfer and pricing, to primarily address risk mitigation.

Transferring risk isn't enough

As the world propagates climate risk with more carbon entering the atmosphere, previous estimations of risk exposure are probably wrong, thus just transferring risk is no longer enough.

The aforementioned Florida flooding situation has, as predicted, increased flood losses in the state from US$1.98 billion in 2019 to US$2.94 billion today in 2050.

The corresponding premium increase of approximately 50 per cent since then has made flood insurance unaffordable for many residents, and subsequently, large portions of (re)insurers' books of business unviable.

Similarly, the Californian wildfires in 2018 triggered the beginning of an insurability crisis, for which many homeowners would have lost coverage, were it not for state government intervention.

Underwriters can act to mitigate the economic disruption within and beyond areas immediately affected by such disasters by acting as agents of risk, customer consultants, and partners to the public and social sectors.

They need to better understand the chain of events of specific climate hazards for different sectors and geographic areas to identify market opportunities.

This will further improve business interruption solutions by protecting businesses against systematic catastrophes, such as extreme temperatures which can kill livestock, reduce crop yield and limit outdoor working hours.

Beyond this, at a macro scale, risk mitigation is about immense capital allocation and reallocation.

Underwriting teams need to think through the price signals they send to divert capital away from risky assets that promote perilous behaviour, to eradicate risk rather than just transfer it.

Investment strategies

Together with this, it is increasingly important for (re)insurers to simultaneously evaluate investment allocation strategies and underwriting portfolio exposure to physical and transitional climate risk.

As the economy attempts to shift towards long-term decarbonisation, rapid asset repricing and portfolio volatility may follow, particularly for carbon intensive investments.

(Re)insurers today should look to match risk transfer initiatives with alternative capital from investors with more risk appetite.

For example, back in 2013 the World Bank brought together a hedge fund and reinsurer to insure a Uruguayan electric-power company for US$450 million against drought (which would cripple Uruguay’s hydroelectric production) and high oil prices (which would make power generation costly).

The cover protected both the Uruguayan government and end consumers from exposure to expensive fiscal liabilities, alongside providing cost certainty and budget stability to the state-owned electric utility.

Such partnerships exemplify the strategic and proactive types of initiatives that can manage the ever-increasing scope of risk aggregation and prospective economic impacts, particularly where risks are difficult to insure at reasonable rates.

From a commercial viewpoint, (re)insures need to raise the profile of climate risk in their organisations through clear governance structures to avoid reexperiencing the shortfalls seen in 2020.

A study by ShareAction back then found that no insurer demonstrated leadership across its entire responsible investment and underwriting approach, and almost half the world’s 70 largest insurers received a poor rating for their environment, social and governance (ESG) practices.

(Re)insurers need to ensure significant portions of their portfolio’s support a decarbonised economy to demonstrate their proactive approach to ESG, while limiting liability risks such as legal costs and the reputational damages associated with failing to meet climate risk responsibilities.

In 2020, BlackRock forged the right path within the asset management industry by acting against companies in their portfolio who were making insufficient progress on climate change.

Assessement and mitigation

Furthermore, it is also imperative that ongoing climate risk assessment and mitigation efforts are embedded consistently across (re)insurers' enterprise risk management framework.

The commercial response requires all-inclusive policies incorporating the management of assets, scrutiny of existing business being written and awareness of potential liability from senior management.

(Re)insurers that provide director's and officer's cover must remain informed of climate change developments in this area to shield potential impacts on their portfolio, as there is a growing duty of care on senior management to act in the best interests of protecting the environment.

Separately, the notion of climate change has and will continue to be a source of meaning for employees.

If (re)insurers can put protecting livelihoods, the economy, and the planet at the forefront of their strategic objectives, their ability to attract and retain talent will likely improve, whilst polishing their brand.

Leading on from this, it is equally important that (re)insurance climate analytics evolves beyond conventional risk assessment methods.

Current catastrophe models continue to be closely linked to historical data and developments have been slow to incorporate predictive climate science, making it virtually impossible to forecast future catastrophic events.

This is a big problem given the output from such models form a fundamental part of client's decision-making process, and climate change effects in 2050 continue to alter the probability and intensity of meteorologically linked physical perils.

Scientists within (re)insurance companies need to keep learning about climate sensitivity and emission scenario’s outside the industry, and simultaneously help climate experts in academia and governments understand the difficulty in incorporating this into results.

The most promising avenue rests with climate models based on credible, peer-reviewed research.

These provide forward-looking projections of temperature, precipitation and other weather-related conditions, from simulations of greenhouse gas emission effects on energy and matter in our oceans, atmosphere, and land.

By coupling climate model data with vulnerability assessments, quantified financial losses and future hazard data can be estimated and interpreted by climatologists, data scientists and financial analysts to develop realistic climate scenario-based solutions.

A plethora of opportunity

If this knowledge can be effectively conveyed and utilised by non-scientific experts it could unlock a plethora of analytical opportunity for the (re)insurance industry.

For example, enabling holistic preparation for future climate threats, such as strategic investments in stormwater best management practices and green roofs to mitigate flooding and extreme temperatures.

Such an approach could help identify locations with lower climate risk profiles making it easier for corporations to place key future facilities.

Investors would be able to view risk for the next decade rather than year, with climate variables factored in.

And the broader impact of climate change on the availability of physical peril insurance, cost of capital, and regulatory requirements would be better understood.

Ultimately, proper preparation would put the industry in a strong position to provide insightful commentary on future mitigation strategies, especially if macroeconomic climate implications are stress tested on pricing and portfolio adjustments.

From a societal perspective, (re)insurers' focus must turn to an unappreciated problem area since 2020, insurance affordability.

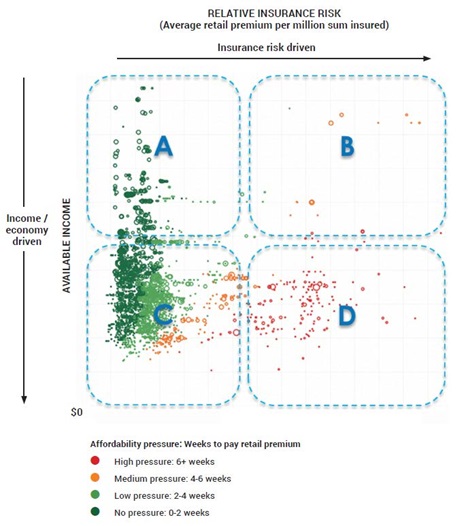

With increasing extreme events from climate change, greater cases of underinsurance and substantial market dislocation have occurred, including rates of self-insurance and requests for disaster relief from the public sector; the issue notoriously impacts high risk areas in lower socio-economic groups (see Appendix D).

Appendix D (Actuaries Institute, 2020)

This shows the average level of affordability pressure across 3000 Australian postcodes; sum insured is reflected by circle size. 12% of postcodes have medium to high affordability pressure. Areas such as Bundaberg (QLD) and Greater Geraldton (WA) fall into quadrants C and D.

Currently there is a lack of clear and recognised affordability measures, however pre-mitigation strategies such as land use planning and stronger building standards can help reduce premiums and navigate new forms of volatility.

The former should make use of enhanced catastrophe modelling and higher resolution data to prevent building development in hazardous risk areas.

Whereas the latter requires a forward-looking approach to ensure dwellings are designed to standards fit for purpose in a changing climate; for example, the impact of southerly shifts in cyclones on newly exposed areas.

Additionally, solutions such as premium funding, changing the frequency of premium payments and parametric insurance can also provide useful alternatives to help improve insurance accessibility.

(Re)insurers should also look to drive resilience to reduce the protection gap in climate-vulnerable countries by working with governments and local authorities.

Public-private partnerships such as Flood Re in the UK, the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, and Australia Reinsurance Pool Corporation have all helped spread loss geographically and through capital bonds, but new reinsurance pools need to be introduced that work more systematically across climate-exposed counties.

The final objective needs to be to enhance the risk profile of populations to maximise insurability, and minimise ongoing government intervention in a cost effective manner.

Conclusion

In conclusion, climate change remains a substantial challenge facing humanity which continues to reshape industries and markets.

(Re)insurers must strengthen their assessment of climate risks while taking strategic actions to mitigate exposures, safeguard the interests of society and serve the foundational purpose of the industry.

Actions such as changing business models, combining catastrophe and climate risk capabilities, rethinking access to capital, reducing the protection gap, and integrating holistic approaches as a part of enterprise risk management efforts will help navigate this uncertainty and seize opportunities as they emerge.

But (re)insurers must act now as the window for an effective response is limited.

Bibliography

- Actuaries Institute, 2020. Property Insurance Affordability: Challenges and Potential Solutions. https://actuaries.asn.au/Library/Miscellaneous/2020/GIRESEARCHPAPER.pdf

- BlackRock, 2020. BlackRock: Our approach to sustainability.

https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/our-commitment-to-sustainability-exec-summary-en.pdf - Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub, 2019. Bushfires and climate change in Australia. https://nespclimate.com.au/wp-

content/uploads/2019/11/A4_4pp_brochure_NESP_ESCC_Bushfires_FINAL_Nov11_2019_ WEB.pdf - Earth Systems and Climate Change Hub, 2019. Tropical Cyclones and climate change in Australia. https://nespclimate.com.au/tag/tropical-cyclones/

- Grieves, T. 2020. Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight: Fusing catastrophe modelling and climate science for more realistic climate risk scenarios, pg. 26. 20210125-if-annual-cat-report.pdf (aon.com).

- Grieves, T. 2020. Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight: Mitigating Market Shocks and Managing Climate Transition, pg. 35. 20210125-if-annual-cat-report.pdf (aon.com)

- Ingham T, et al. 2020. Climate Change: Insurance industry perspectives.

https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/e48423da/climate-change-insurance-industry-perspectives - McKinsey & Company, 2020. Florida Flooding and insurance market failures.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/climate-change-and-p-and-c-insurance-the-threat-and-opportunity - McKinsey & Company, 2020. How a post-pandemic stimulus can both create jobs and help the climate. A low-carbon economic stimulus after COVID-19 | McKinsey

- McKinsey & Company, 2020. Seven Crucial Traits of Physical climate risk.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/climate-change-and-p-and-c-insurance-the-threat-and-opportunity - McKinsey & Company, 2021. How Insurance can help combat climate change.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/how-insurance-can-help-combat-climate-change - NASA, 2021. Is it too late to prevent climate change? https://climate.nasa.gov/faq/16/is-it-too-late-to-prevent-climate-change/

- ShareAction, 2021. New data shows insurance giants driving climate change, biodiversity loss and human rights violations. https://shareaction.org/new-data-shows-insurance-giants-driving-climate-change-biodiversity-loss-and-human-rights-violations/

- Startzel S, et al. 2020. Uniting catastrophe and climate models to enhance risk management in a warming world. 20200921-tp-climate-cat-model-eval (aon.com)• Statista, 2018. Most costly disasters to the insurance industry worldwide 1970-2017. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267210/natural-disaster-damage-totals-worldwide-since-1970/

- The World Bank, 2018. Uruguay buys insurance against lack of rain and high oil prices. https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2018/01/10/uruguay-insurance-against-rain-oil-prices

- Van Vuuren, et al, 2011. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z

- Vittal Hari, et al, 2020. Increased future occurrences of the exceptional 2018–2019 Central European drought under global warming. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-68872-9

Comments

Remove Comment

Are you sure you want to delete your comment?

This cannot be undone.