Vol 46: Issue 2 | July 2023

IN SHORT

- Speculation about Australian and New Zealand concussion-related cases has become a reality, with at least two high-profile lawsuits looming.

- Players often have some insurance in place but CTE often only emerges after they retire and a diagnosis can only be confirmed by autopsy.

- Legal action and insurance claims may focus on the liability of codes in preventing repetitive head impacts.

‘Punch drunk’ is a term that has been thrown around boxing circles for almost a century.

First coined by pathologist Dr Harrison Martland in a 1928 paper on the physical effects of boxing, punch-drunk syndrome became synonymous with combatants staggering in the ring and developing speech and behavioural problems in later life.

It was re-termed dementia pugilistica — literally ‘boxer’s dementia’ — and then became more popularly known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, in the 1940s.

Whatever the label, the premise was the same: anyone subjected to multiple head knocks over an extended period of time was at risk of developing this fatal condition.

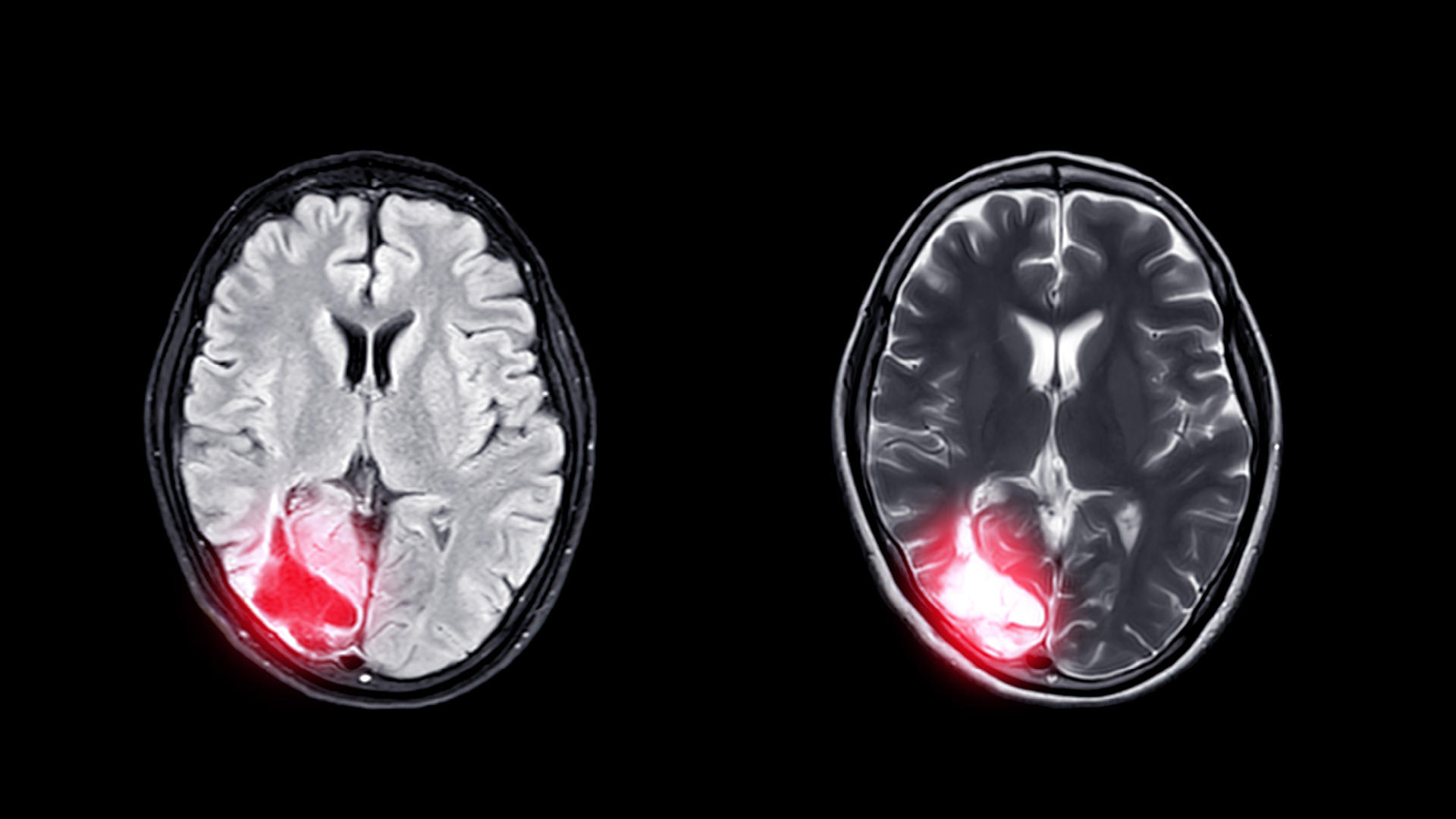

A degenerative disease, CTE causes the death of nerve cells in the brain. The early stages are commonly marked by mental health and behavioural issues, such as depression, anxiety and aggressive tendencies.

As the condition worsens, it increasingly impacts thinking and memory, with symptoms including speech difficulties and problems with movement and balance.

It was American football, or gridiron, that catapulted CTE into the spotlight.

A string of suicides involving former National Football League (NFL) players began with Andre Waters, who died in 2006, followed by Dave Duerson (2011) and Junior Seau (2012).

Autopsies revealed all three had CTE. Then, awareness reached a crescendo with Concussion, a 2015 Hollywood movie based on a true story that saw Will Smith play Dr Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist among the first to publish CTE findings related to NFL players.

However, this disease has not been confined to the United States, the NFL and boxing.

In recent years, cases and lawsuits have sprung up globally. Where billions of dollars have been poured out for compensation in the US, differing policies between sporting codes and countries ensure that claims and settlements remain inconsistent worldwide.

Fade to black

New Zealander Geoff Old, 67, cannot remember a single second of his glittering rugby union career.

That period from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s included a tour of Wales and a tour of France.

It even included the phone call that confirmed him as an All Black — a go-to moment immortalised in the All Blacks Experience in Auckland that shows a compilation of past players sharing their stories.

On a visit to this popular interactive attraction a few years ago, Old broke down when he realised he couldn’t recall his personal experience. For Old, memories have disappeared in much the same way Ernest Hemingway wrote about bankruptcy: “Gradually, then suddenly.”

“Sometimes, and especially in the beginning, it’s not dangerous. It’s just so odd,” says Old’s partner of 20 years, Irene Gottlieb-Old. “It’s like out of the blue. If you think you know [that person], you go, ‘Wow, that’s different’. If it’s making a decision or physically moving from one place to another, [you use] a workaround to get to the same place.” This could be dinner plans, travel destinations or something as simple as what to wear.

Of rugby, she says: “It’s a tough sport. None of them walk in with rose-coloured glasses, but nobody told them they would end up with a brain disease two decades later.”

Old is not covered under the no-fault compensation scheme operated by New Zealand’s Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC), according to Gottlieb-Old.

Rugby Australia’s National Risk Management and Insurance Programme, which Aon underwrites, currently offers a payout of A$300,000 for permanent disability that is not paraplegia or quadriplegia (where the payment is A$750,000).

Old’s faculties have disintegrated to the point where his communication with the Journal was limited, but his New Zealand accent was unmistakable. Gottlieb-Old recalls what has been lost: “Just a real gentle, lovely, kind-hearted, funny man … and it’s as if the excitement fell off his face. I don’t know how else to share [it]. He became dull and maybe a little combative, but it’s more from frustration. I can analyse the behaviour but, for the most part, everything became a lot more difficult. It was not easy. I do feel a bit like a survivor.”

Gottlieb-Old is an American-born businesswoman who met the former All Black in Colorado after his time as technical director of USA Rugby. She estimates Old has had symptoms of CTE for 18 of the 20 years they have been together.

“We’ve lived through so much tragedy, scary things and actually laugh-out-loud, funny stuff,” she says. “I’ve been running him literally around the world looking for support, [searching for] like minds or new technology. Something to help. Something to try to put our finger on what was going on.”

Ticking time bomb

Figures from New Zealand’s ACC show there were at least 1,934 new claims for rugby union-related concussion / brain injuries in 2022. Those figures are down from three years earlier. In 2019, the ACC saw 2,641 new claims, 366 of those being females.

Active costs in compensation and treatment are registered at NZ$6.75 million. However, a spokesperson for the ACC says: “Very few concussion-related claims lead to diagnoses of CTE.

The ACC has provided cover and entitlements for fewer than four probable diagnoses of CTE. None of these claims were related to rugby.”Diagnosing the condition is a stumbling block.

“Currently, CTE can only be diagnosed by examination of the brain at autopsy,”

explains Dr Michael Buckland, head of the department of neuropathology at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney. “In fact, the current definition of CTE is based on the finding of an abnormally folded protein called tau in specific regions of the brain.”

Over the past year, the Boston University CTE Center has conducted an extensive postmortem study of 376 former NFL players. In February this year, it announced that 345 of those players — or 92 per cent — were found to have CTE.

Day of reckoning

What do these numbers and cases mean for insurance claims in Australia and New Zealand?

“It is difficult to speculate,” says Dr Annette Greenhow, a legal academic at Bond University. “In my opinion, as the rumours of litigation were circulating for several years, the sports involved have likely had their legal teams fully engaged in preparing for the eventual filing of claims.”

Former All Black Carl Hayman is one of many former rugby union players — most of them from Britain and Ireland — taking legal action against World Rugby.

Players from other sporting codes are also joining the growing list of claimants. London-based law firm Rylands Garth announced in April that it would formally start a lawsuit on behalf of 260 rugby union players, 100 rugby league players and 15 soccer players, who allege that authorities in their respective sports “were negligent in failing to take reasonable action to protect players from permanent injury caused by repetitive concussive and subconcussive blows”.

Bill Sweeney, CEO of the United Kingdom’s Rugby Football Union, has previously stated that making rugby risk free is a “journey with no conclusion”. Regarding insurance claims, Sweeney adds: “I’ve got no reason to believe we wouldn’t be covered for this, but we’re not going into that detailed discussion until we see the nature of what is being submitted.”

On this side of the world, the Australian Football League is facing a class action by dozens of former players seeking compensation for the “serious damage” allegedly caused by concussion-related injuries during their careers.

“Now that this has happened, the outcome will very much depend on the attitude of the sport’s governing body and whether it adopts a strategy of working towards a settlement on a ‘no admission of liability’ basis, or whether it adopts a defensive litigation strategy pushing for a full-blown hearing on the issues,” says Greenhow.

“If matters proceed to trial, then one of the procedural matters to consider is discovery, where each party is required to disclose relevant information with respect to the particulars of the claim, the state of scientific understanding at the relevant time, and what was known or ought to have been known about the risk of harm.”

Wait and see

In the meantime, despite his deteriorating condition, Geoff Old has lost none of his passion for rugby union and, more particularly, the performance of the All Blacks.

“He follows everything,” says Gottlieb-Old. “And what he does is he watches the games and he watches it like a coach, and he makes notes and he analyses this and that. It’s almost like he’s still working.”

That will most certainly include this year’s Rugby World Cup, which is being played in France and sees the All Blacks chasing a record fourth title. But what happens in the ensuing years is yet to play out.

What is CTE?

By Dr Michael Buckland

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a degenerative brain disease with some similarities to Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia. The only known risk factor for developing CTE is exposure to repetitive head impacts (RHI), both concussions and sub concussive impacts.

In the past, CTE was thought to occur only in ex-boxers; however, we now understand that CTE occurs in a wide range of sportspeople exposed to RHI, as well as people who are exposed to RHI due to their work (military veterans, for example) or illness (people with very bad epileptic seizures).

In Australia, CTE has been identified in ex-players of rugby union, rugby league and Australian Rules football.

There are many ways that CTE can manifest in life. In earlier or younger cases, people may have symptoms such as anxiety, depression, aggression and impaired impulse control. In later cases, in older people, the symptoms may mimic Alzheimer’s disease, with difficulties in thinking and short-term memory.

Changing the (Australian) rules

Dramatically reducing instances of head-high contact will be one of the legacies of departing Australian Football League (AFL) chief executive Gillon McLachlan, with the league having announced a crackdown on dangerous tackles in the 2022 season.

But that hasn’t eliminated the lawsuits pertaining to concussion and CTE claims.

In March this year, Western Bulldogs 2016 premiership player Liam Picken launched legal action against the AFL, his former club and club doctors in regard to ongoing concussion symptoms that plague his physical and mental health. Picken, now 36, retired four years ago on medical advice.

Max Rooke played 135 games for the Geelong Cats, including premierships in 2007 and 2009. He has been named as the lead plaintiff in a class action involving 60 former AFL players who played between 1985 and 2023. Court documents lodged by Margalit Injury Lawyers allege Rooke was concussed up to 30 times and that the AFL “breached the duty owed to the plaintiff”.

The AFL has pledged A$25 million for an ongoing study into the long-term effects of concussions and head knocks on players in both the men’s and women’s competitions.

Among a range of measures are the AFL Brain Health Initiative, a longitudinal research program that will monitor the brain health of AFL and AFLW players across their careers and into later life and a new AFL concussion governance structure.

This follows the 2021 introduction of a mandatory minimum 12-day post-concussion recovery period for all players and medical substitutes where a player is deemed medically unfit to continue playing.

The changes have been introduced too late for former AFLW player Heather Anderson, who in July 2023 became the first female professional athlete diagnosed with CTE.

Anderson played seven games for the Adelaide Crows before retiring in 2017. She took her own life in November 2022.

Read this article and all the other articles from the latest issue of the Journal e-magazine

Comments

Remove Comment

Are you sure you want to delete your comment?

This cannot be undone.